Q. How would you style the past tense of “green-light”—“green-lighted” or “greenlit”?

A. Although Merriam-Webster.com’s dictionary includes the verb “green-light” as a subentry under its entry for the noun form “green light,” it doesn’t conjugate it. But you could consult that same dictionary’s entry for “light” as a verb and choose the first-listed form of the past tense there: “lit” (“lighted” is an equal variant). You might also take a look at Merriam-Webster’s usage note on the subject, which explains that “green-lighted,” once the dominant past-tense form, has recently been losing out to the one-word “greenlit.”

If you’re comfortable getting ahead of recent trends, you could greenlight “greenlit.” If you’re not ready for that, retain the hyphens in the verb forms (“green-light,” “green-lit”). Until Merriam-Webster removes the hyphen from its entry for “green-light” as a verb, that’s what we’d probably do.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. With a compound subject, does the verb number change when the conjunction “and” is replaced by “and then”? For example: “Swimming in the ocean and then running a marathon require/requires great endurance.” I’m told CMOS 5.138 applies and the verb should be plural (“require”). But it seems to me “and then” has combined the two actions into a sequence (as one) which would take the singular “requires.”

A. Two subjects joined by and can sometimes be considered singular. The test is whether the subjects express a single idea or more than one. In your example, what requires endurance is the combined action of swimming in the ocean and running a marathon—a continuous feat of athletic activity. The adverb “then” makes this clear.

But adding “then” won’t always make a plural compound subject singular. Consider the following sentence, in which the subjects clearly take a plural verb: “A bandage and then an ice pack were placed on the wound.” On the other hand, you can write a sentence with a compound-but-singular subject without the help of “then.” For example, “Peanut butter and jelly is the best thing to happen to sandwiches since sliced bread.”

So it’s best to consider such sentences on a case-by-case basis.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Often lately, in drafts I’m editing as well as in emails from colleagues, I’ve seen “below” as an adjective—for instance, “the below example.” This looks and sounds wrong to me. To my further dismay, I just noticed it in an example in my agency’s writing guidance (which I’m partly responsible for updating). CMOS 5.250 doesn’t address this matter, but when I searched the Manual for “the below,” there were no results. Merriam-Webster lists “below” as an adjective and shows it being used before a noun (“the below list”)—but I’ve been told Merriam-Webster presents common usage rather than good usage. The American Heritage Dictionary, which I understand is more prescriptive, lists “below” only as an adverb or preposition. Before I do battle about “below” in our writing guidance, I’d like to know your opinion. Thanks in advance for your thoughts.

A. We agree that “the example below” would generally be preferable to “the below example”; the absence of below as an adjective in at least one major dictionary is a good piece of evidence in favor of such a preference. The OED provides more evidence in your favor. That dictionary includes the adjectival sense, but with this label: “rare in comparison with ABOVE adj.” And it defines both below and above as adjectives only in the sense of “below-mentioned” and “above-mentioned” (or “-listed,” “-described,” etc.).

This accords with how below and above as adjectives are both defined in Merriam-Webster, so we can conclude that they’re a sort of shorthand for adjectival compounds like “below-mentioned” and “above-mentioned”—in which below and above, it should be noted, function not as adjectives but as adverbs that modify the participle mentioned.

(The words below and above are also used in this way as nouns—as in “refer to the below” or “none of the above.” Both the OED and Merriam-Webster include entries for these terms as nouns, and the OED makes the same note as it does for the adjective that below is rare in this sense relative to above.)

Why below seems less comfortable than above as an adjective (or as a noun) is a matter for linguists. In the meantime, you might insist that “the below example” is an uncommon usage that’s likely to strike the wrong note for at least some readers, as it did for you. Fortunately, it’s an easy problem to fix (i.e., simply move “below” so that it follows the noun).

(Feel free to cite the answer above if it will help you to make your case.)

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. CMOS 5.195 says that “compare with” is for literal comparisons and “compare to” for poetic or metaphorical comparisons. What is a “literal comparison,” and how does it compare with a “poetic or metaphorical comparison”?

A. A literal comparison examines two things relative to each other in a process that might turn up both similarities and differences (but often with an emphasis on the differences); you’ve demonstrated this usage in your question (“how does it compare with . . . ?”). We might also, for example, compare The Chicago Manual of Style with the AP Stylebook.

In a poetic or metaphorical comparison, the point is to note similarities between things that are not necessarily similar—as in Shakespeare’s “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” People and summer days aren’t literally alike; figuratively, however, it’s a different story (e.g., they might both be “lovely” or “temperate”). This type of comparison—with “to” rather than “with”—is useful for suggesting similarities of any kind: “Please don’t compare me to him. We’re not at all the same.”

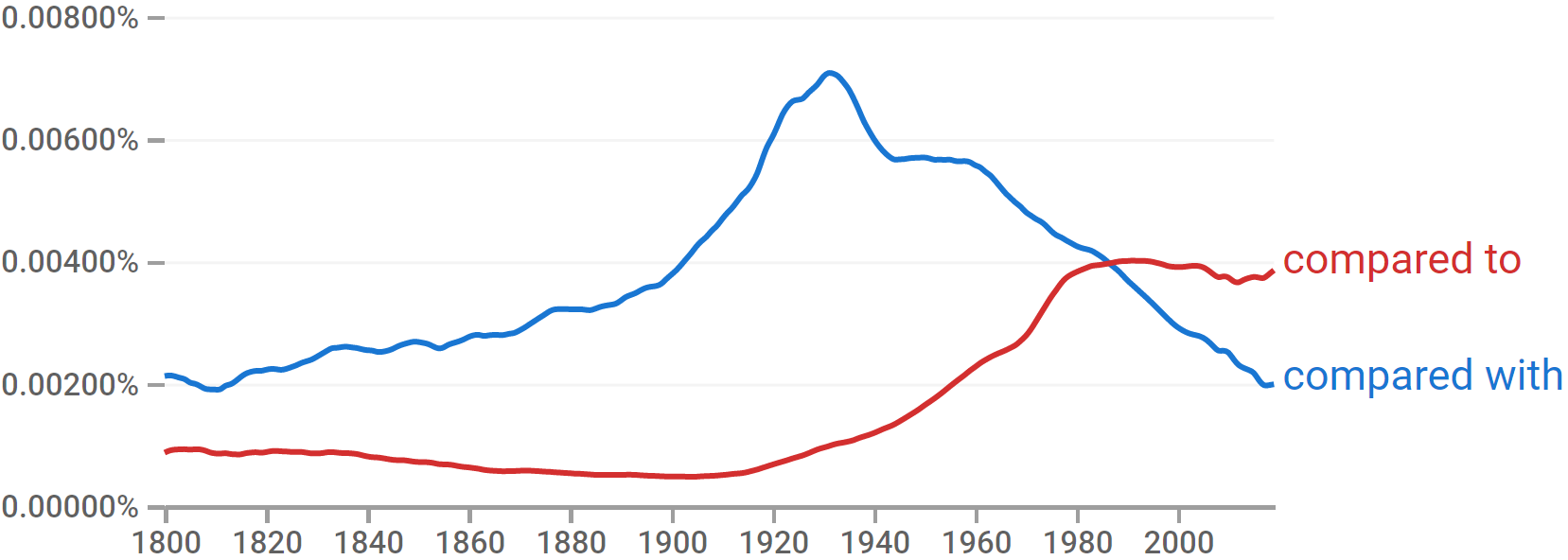

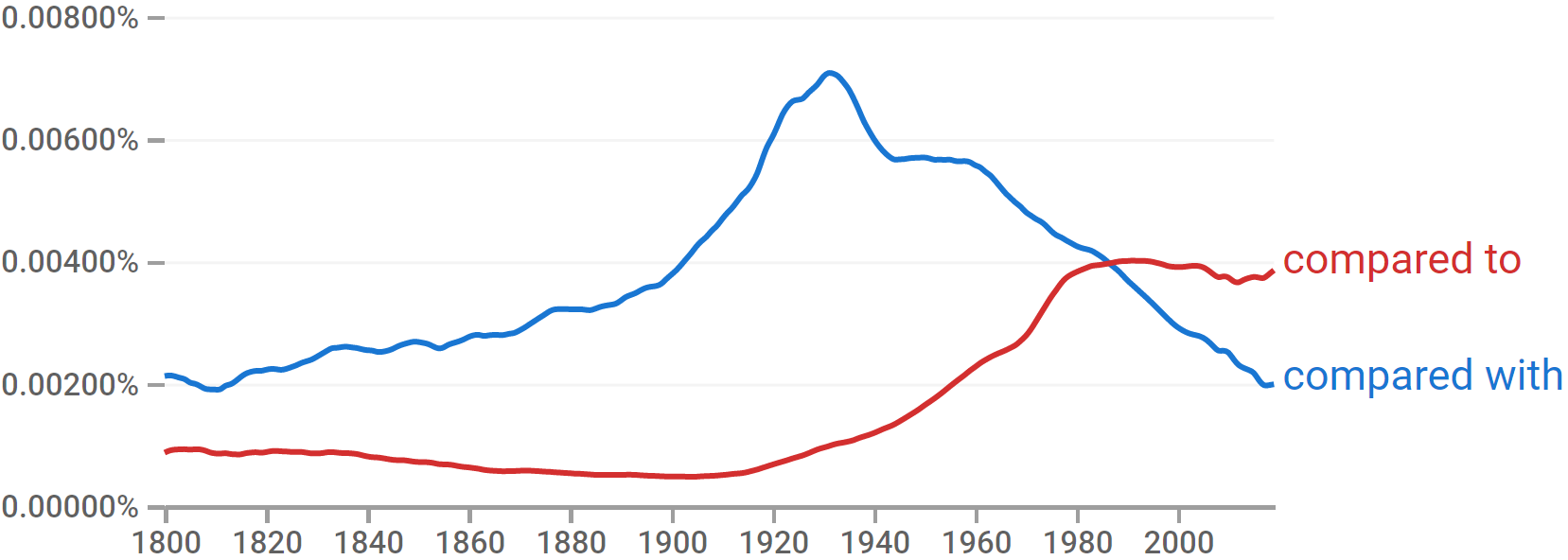

For what it’s worth, the “to/with” distinction seems to be fading, as this Google Ngram comparing the frequency of “compared with” with that of “compared to” in books published in English since 1800 suggests (showing “to” overtaking “with” in the mid-1980s—a reversal that happened in the mid-1970s in American English but thirty years later in British English):

Adjusting the terms to “compare to” vs. “compare with” or “compare this to” vs. “compare this with” (and the like) shows a similar trend. If you’re a copyeditor, you might choose to enforce the distinction in formal prose but not necessarily in fictional dialogue and the like.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Is the term “log in to” or “log into” when a user is connecting to a computer?

A. Though the right answer depends on a subtle distinction that’s often overlooked (with, let’s be honest, no significant loss of meaning), formally correct usage would call for “log in to” (with “in to” as two words). The same goes for logging on—or signing in or signing on—to something. In each case, the word “in” (or “on”) forms a part of the verb phrase, where it functions as an adverb rather than as a preposition. For some additional considerations, see CMOS 5.250, under “onto; on to; on.”

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Should it be “Nobody but she and Sandra knew if he was lying” or “Nobody but her and Sandra knew if he was lying”? Surely, nobody but the Chicago Q&A will know which is correct—or if neither is!

A. Choose the second version: “Nobody but her and Sandra knew if he was lying.” Rearranging the words in the sentence can help to confirm the right answer: “Nobody knew if he was lying but her and Sandra.” It should now be clear that “nobody” and “he” are the subjects of the verbs “knew” and “was lying,” respectively, whereas “her” and “Sandra” are objects of the preposition “but.” So “her”—which is in the objective case—is correct.

[Editor’s update: It turns out we were a bit hasty with our answer. It’s true that the word “but” can act as a preposition in “nobody but [pronoun]” constructions—as it does in our reordered version of the original, in which the phrase beginning with “but” has been moved to follow the verb “knew.” In that version, the objective “her” is always correct: “Nobody knew if he was lying but [i.e., except] her and Sandra.” But according to Bryan Garner, when the phrase with “but” precedes the verb, “but” can be said to be acting as a conjunction; accordingly, “she” would be the “traditionally” accepted choice in the sentence as originally worded: “Nobody but she and Sandra knew if he was lying.” The version with “her” (as in our original answer), meanwhile, has achieved stage 5 in Garner’s language-change index: “universally accepted (not counting pseudo-snoot eccentrics).” In sum, either answer is acceptable. For the full explanation (and the “dissenting opinion” that supports our original answer with, according to Garner, “impeccable” logic), see Garner’s Modern English Usage, 4th ed. (Oxford University Press, 2016), under “but: D. Preposition or Conjunction.”]

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. For the labels on a wall at an art exhibit, should it be “courtesy of the artist” or “courtesy the artist”? I am under the impression that “courtesy of” is acknowledgment as well as thanks to the second party for providing something.

A. The phrase “by courtesy of” is typically shortened to “courtesy of.” In credit lines and the like, where space tends to be limited, the phrase has often been further shortened to “courtesy.” In the context of giving credit, all three forms mean the same thing (something like “thanks to” or “kindly provided by”). Pick one and be consistent, though “courtesy of” is probably the best choice in most contexts, room permitting.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Is it “companies and people who dodge taxes” or “companies and people that dodge taxes”? What if the order is changed?

A. The relative pronouns “who” and “that” can both be used to apply to people or groups thereof, so “companies who,” “companies that,” “people who,” and “people that” are all strictly correct. However, readers tend to expect “that” with an abstract collective noun like “companies” and “who” in references to people—collective or not. When the two nouns are paired, choose the relative pronoun that would fit best with the nearest antecedent: “people and companies that,” but “companies and people who.” The choice is somewhat arbitrary, but at least some readers are likely to appreciate the distinction, particularly in that last pairing.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. I have run across the phrase “comprised of” multiple times in a book I’m editing. Depending on context, Google Docs wants me to use “composed” or “consisting” or “comprises” or whatever fits. I know M-W says that while the phrase is not technically incorrect, it does sometimes receive scrutiny. Does CMOS have an official standpoint on its use? Thanks!

A. See CMOS 5.250, under “comprise; compose”: “Use with care. To comprise is ‘to consist of, to include’ {the whole comprises the parts}. To compose is ‘to make up, to form the substance of something’ {the parts compose the whole}. The phrase is comprised of, though increasingly common, remains nonstandard. Instead, try is composed of or consists of.” Another option: “is made up of.”

Some of the decisions an editor makes will always be directed at other editors—or at readers who think like editors. “Comprise” is one of those words that, if you misuse it, risks drawing the attention of anyone who pays close attention to dictionaries and usage manuals (not to mention whatever their screens are telling them). So take the hint from Google and revise to avoid “comprised of”—except, for example, in a direct quotation or as an example of dialogue that reflects how many people actually use the term.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Parenthetical material is usually invisible to the grammar of the rest of the sentence, so should it be “a” or “an” in the phrase “a (appropriate) joke”?

A. Although almost anything can be placed inside them (Is it Friday yet?), parentheses don’t make the words they enclose literally invisible. Readers are still obliged to read what’s inside along with the rest of the text. So write “an (appropriate) joke,” which will spare us from reading “a appropriate joke,” a phrase that, stylistically speaking, would be inappropriate.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]