Q. Should we apply headline-style capitalization to band names and other proper names containing prepositions? Is it Rage against the Machine or Rage Against the Machine, for example? Thank you!

A. Good question! Normally, yes, the capitalization rules for titles of books and other works (as described in CMOS 8.159) would apply equally to other capitalized names, including names of organizations and musical groups.

Accordingly, articles (a, an, the), common coordinating conjunctions (and, but, for, or, nor), and prepositions (of, for, with, etc.) would all be lowercased in the middle of a name. For example, the National Institutes of Health, Sly and the Family Stone—and Rage against the Machine.

But we’d allow an exception in that last case. Against may be a preposition, but it’s just as long as Machine, putting lowercase at odds with the rest of the name. And the sources that have written about that band would have tended to follow some variation of AP style (the main US style for journalists), which capitalizes prepositions of four letters or more. “Rage Against the Machine” is therefore more likely than “Rage against the Machine” to look right—at least to anyone who hasn’t just edited a forty-five-page bibliography to conform to Chicago style.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. I’m having trouble explaining to my organization why “the internet” is now lowercase “i.” We do follow CMOS style, but the Internet Society and some others are insisting otherwise. Can I get an explanation that I can use? Not seeing any in the manual.

A. An explanation is beyond the scope of CMOS, but here’s a summary: In ordinary usage, internet with a lowercase i has been common since at least the introduction of the iPod (in 2001; note that lowercase i). And because ordinary usage tends to determine how tech-related neologisms are styled, many guides now prefer lowercase internet—including not only CMOS but also the latest from Microsoft and Apple (computer tech), AP (journalism), APA (psychology), and AMA (medicine).

Meanwhile, documents published by W3C and related organizations that develop or maintain the standards that determine how it all works still tend to refer to the Internet when they mean the worldwide network of computers (but internet when referring to any interconnected network). And as recently as 2019, Internet was still more common in published books than internet—though the trend toward lowercase is clear.

So the usage preferred by specialists may be less common than it once was, but it’s far from defunct. And according to CMOS 7.2, any discipline-specific preference (which would extend to capitalization) should be respected.

All of which is to say that if you’re editing for the Internet Society, which is in the same league as W3C, then you should accept the capital I. For most other types of organizations, common usage will likely be the better choice.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Would “secretary of homeland security” be lowercase in a sentence without that person’s name?

A. Just as you’d refer in Chicago style to a president of the United States or other country with a lowercase p (as in this sentence), you’d use a lowercase s when referring to a secretary of homeland security.

But note that the generic phrase “homeland security” (like “transportation,” “state,” and other such terms) becomes a proper noun when it refers to the administrative body—as in the Department of Homeland Security, or Homeland Security for short.

So you’d refer to the secretary of the US Department of Homeland Security. But this can get tricky: Does “homeland security” in “secretary of homeland security” refer to the department or only to the role? If in doubt, capitalize (“secretary of Homeland Security”). See also CMOS 8.22 and 8.63.

And before a name, secretary would be capitalized, as in US Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, or Secretary Mayorkas.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Hello! I’m wondering if you can give me some guidance on flight numbers. Chicago doesn’t seem to mention them, but flights appear to be capitalized when they follow the airline’s name from what I can see online—for example, Pan Am Flight 103 (the one in the Lockerbie bombing). So I’m thinking a flight should be, say, “flight 900” when used alone (as in “I took flight 900 to Geneva”), or Big Airline Flight 900 when it appears after an airline’s name. Does that sound about right to you? Many thanks!

A. In strict Chicago style, flight numbers would be lowercased—like room numbers, page numbers, and other such identifiers. Accordingly, we’d write “Pan Am flight 103” and, for subsequent mentions, “flight 103.” That’s the style Britannica follows in its article on the tragedy. According to this usage, “Pan Am” is a proper noun, whereas “flight 103” is not.

But you’re right that many sources capitalize flight numbers. If you’re going to go that route, however, you should still treat the airline name and flight number as separate terms, which would require a capital F even when the flight number is used alone: Pan Am Flight 103; Flight 103 (but the flight).

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Would CMOS lowercase the noun preceding the number in each below? Yes or no?

He was called to aisle 8.

The meeting was at building 50.

The accident happened on interstate 90.

Tom got off at exit 12.

Holyfield fell in round 4.

The cashier stole cash from register 7.

The incident happened at terminal 1.

Thank you.

A. Words like “interstate” and “highway” are generally considered part of the name and capitalized: Interstate 90, Highway 66. But all the other terms in your list—from “aisle 8” to “terminal 1”—would be treated as generic and lowercased.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Do you lowercase occupational forms of address like “waiter,” “driver,” “bartender,” and “cook”? It seems that I got different opinions on various websites. Thanks for your input.

A. None of the terms you mention would normally be capitalized in direct address, even when standing in for a name:

Where are you taking me, driver?

Hey, bartender, where’s my drink?

But if the occupation can also be used as a title, capitalization is the norm:

How bad is it, Doctor?

What’s the rush, Captain?

Either convention can be broken, however.

For example, capitalization would make sense for a fictional character known by occupation alone, even if the occupation isn’t also a title—as in the case of the character known as “Driver” in the novels Drive and Driven, by James Sallis (Poisoned Pen Press, 2005 and 2012). And titles that aren’t being used literally are less likely to merit capitalization: What’s up, doc?

For some additional considerations, see CMOS 8.34–37.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. When indirectly referring to Catholic nuns, should the term “sisters” be capitalized?

A. According to Merriam-Webster, “sister” is “often capitalized” when referring to a member of a religious order, Catholic or otherwise. CMOS takes that “often” as permission to use lowercase: “The sisters left the convent at noon.”

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Does CMOS allow random capitalization in poems?

A. We would, provided the randomness worked on some level. If a publisher has accepted the poem, then it probably does. A copyeditor might query any choice that doesn’t seem to be intentionally random—on the off chance that it might be a mistake—but otherwise, it’s usually up to The PoET.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Hello! I work in marketing, and I’m wondering if lowercasing the words “off” and “under” in these headlines is correct: “50% off Body Wash” and “Gift Sets under $40.”

A. If you’re in marketing, capitalize both of those words. Why be quiet about savings?

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Debating with an editor over capitalization of the word bicentennial. When it’s an adjective (“bicentennial year”), I agree that no cap is needed, but I contend that when it’s a noun (“the Bicentennial”), a cap is needed. Agree—or not?

A. The noun bicentennial, like anniversary or birthday or even golden jubilee, is normally lowercased. But if you’re referring to a specific bicentennial, like the one the United States celebrated in 1976—“the Bicentennial”—a capital B might be warranted. Or so it seems in hindsight.

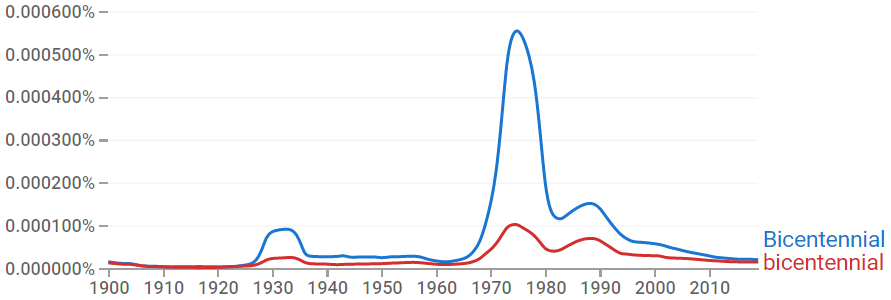

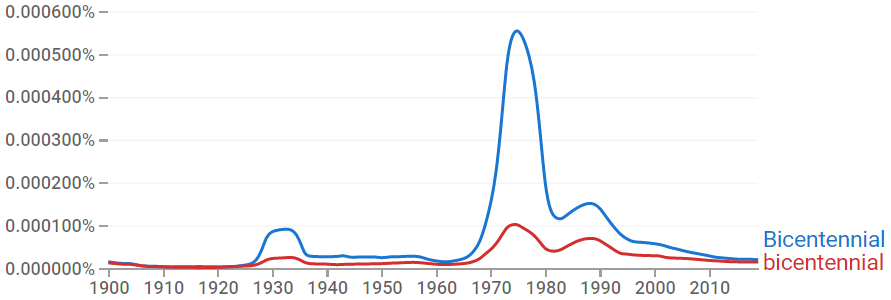

According to a Google Ngram comparison of the lowercase b and capital B forms of the word, there have been three notable jumps for “Bicentennial” in books published in English since 1900:

The two biggest bumps align with major bicentennials in the US (1976) and France (1989). The third peak—ca. 1932—corresponds to the bicentennial of George Washington’s birthday. (The ngram doesn’t tell you any of this—and there are other possibilities—but it’s fun to guess.)

In a publication that discusses one of the national bicentennials, a capital B would make sense. But note that both nouns and adjectives would qualify: the US Bicentennial, the Bicentennial celebrations in the US.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]