Q. Good morning! We’re wondering what to do with the word “but” on the front cover of our newest release: “Present, but Not Counted.” Is it acceptable to cap “But” on the front cover because it looks better than a lowercase “but”? The title in the running heads is in small caps, so no issue there. Citations and references to this title would of course use a lowercase b, but is there a rule about cover text? Or do we have some liberty? Thank you very much.

A. You have some liberty. As your question suggests, the rules in CMOS for capitalizing titles of works apply only to titles that are mentioned or cited in text, notes, bibliographies, and so on. So you can go ahead and put But instead of but on the cover—and on the title page if you prefer. In both places, design takes precedence over the style for text.

But you don’t need to throw out the rules entirely. Instead, you can use the design rather than capitalization alone to de-emphasize words (like but) that would normally be lowercase in a title.

For example, the cover of the 2022 memoir by musician William “Billy Boy” Arnold (written with Kim Field and published by the University of Chicago Press) features all caps for the title words except for of, which is lowercase and italic (and in a different font and lighter color):

When mentioned or cited, that would be The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold, not THE BLUES DREAM of BILLY BOY ARNOLD.

[This answer relies on the 18th edition of CMOS (2024) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. How should one style the title of a work in a discussion not of that work, but of its title. As an example, consider the following sentence:

The novel’s title, “Pride and Prejudice,” refers to a pair of traits seen in all of its characters.

Should the title be set in roman and within quotation marks because it is a phrase being mentioned (rather than used)? Or does the fact that it IS a title prevail, so that it should be italicized and without quotation marks? Or perhaps some tertium—or even quartum—quid? My sense is that because in that sentence its referent is not Austen’s book itself but the character flaws that recur in its plot, the italics would be inappropriate. Do I have that right?

A. You might be overthinking this. The novel’s title is Pride and Prejudice, a three-word italic phrase that names a pair of traits exhibited by many people, including the characters in that book. Chicago-style italics for book titles doesn’t prevent you from discussing what the words mean.

But if you really want to get your readers to home in on the title words as words, try something like this: “The nouns in the novel’s title, pride and prejudice, refer to a pair of traits . . .” or “The nouns in the novel’s title, ‘pride’ and ‘prejudice,’ refer to a pair of traits . . .”

For the use of italics or quotation marks to refer to words as words (either treatment is correct), see CMOS 7.66.

[This answer relies on the 18th edition of CMOS (2024) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. In the headline “Rack ’em Up and Play,” would Chicago support ’em or ’Em? (It’s for an article about a billiards-themed mobile game. We follow Chicago, so our headlines are always in title case. And we have a casual style, hence the contraction.) I’m consumed by indecision. On the one hand, ’Em is technically a pronoun, standing in for Them, and pronouns regardless of length are capitalized in headlines. On the other, I get stuck on the fact that the initial letter of the full word is what would be capitalized, and that initial letter is removed by the contraction. No initial letter, no capital? Aesthetically the lowercase option looks better to me, but other colleagues have said lowercase looks like a mistake to them. Help!

A. Our vote would be to apply an initial capital: Rack ’Em Up and Play. The similar contraction ’twas is usually written ’Twas at the beginning of a sentence (as in the opening line of that famous nineteenth-century American poem: ’Twas the night before Christmas . . .), even though the T in ’Twas would be lowercase if the contraction were to be spelled out (It was . . .). In other words, there’s at least one well-known precedent for ignoring an initial apostrophe for the purposes of capitalization.

[This answer relies on the 18th edition of CMOS (2024) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Hello. Looking for a bit of clarification on headings with parentheses. Should we avoid them? If parentheses are used, what is the proper way to use them in headline style? For example, is “Your Guide to College (And Beyond!)” the correct way to list this chapter title/heading? Thank you.

A. Parentheses are fine to use in a heading or title of any kind, provided you have a reason to use them; when you do, the punctuation marks are usually ignored when applying headline-style capitalization. For example, Chicago style would be to lowercase “and” in the title of R.E.M.’s 1987 hit song “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine).” Such capitalization isn’t currently covered in CMOS, but the logic is the same as it would be for an em dash used in place of parentheses, as in “Your Guide to College—and Beyond!” (see CMOS 8.164). For the periods in “R.E.M.,” an exception to our rule for initialisms in all caps, see 10.24.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Would it be “the Color Purple musical” or “The Color Purple musical”?

A. The musical version of The Color Purple would be referred to as “the Color Purple musical”—where “the” is part of the surrounding text (and the The in the title has been omitted). A “the” belonging to the text could also be used before a title that doesn’t include an initial The. For example, a musical version of Star Trek might be referred to as “the Star Trek musical.”

Or consider other scenarios where a title that does include an initial The is used attributively (i.e., modifies another noun—like musical in the examples above). If you were to retain the The in the following example (where the title modifies character), the result would be clearly awkward:

Which Great Gatsby character do you dislike most?

not

Which The Great Gatsby character do you dislike most?

There’s no “the” at all in the first version of that example—which would also be true if you were to refer to “a Color Purple musical,” where the indefinite article “a” displaces the definite article The in the title. In general, when the title of a work is used attributively, be prepared to omit an initial The in favor of the surrounding text. See also CMOS 8.169.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Is it correct to italicize the word “Titanic” when referring to the movie, or do the italics of a ship name and movie title cancel each other out (assuming quotation marks don’t get involved)? Thanks!

A. Normally, the italics would cancel each other out, as described in CMOS 8.173, which recommends so-called reverse italics—that is, roman—for the name of a ship within the title of a book or other italicized title. But reverse italics wouldn’t work when the name of the ship is the only word in the title. Instead, use italics to refer to the movie Titanic just as you’d use italics to refer to the Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Titanic.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. If the words of a book title are lowercased, do you uppercase them in the bibliography? The CMOS standard for capitalizing the words of a book title in the bibliography are, by and large, the standard of most publishers. So, if a publication veers from that, do you retain the original way of capitalizing (or not) the title? Or do you change it?

A. We apply headline-style capitalization to any book title, whether it’s mentioned in the text or cited in a note or bibliography entry. For example, we’d refer to the Kristina McMorris novel Sold on a Monday (Sourcebooks Landmark, 2018) exactly like that—despite the all-lowercase title on the cover and title page, which this detail from the latter shows:

The same would go for titles styled in all caps on the cover or title page, which we’d render in upper- and lowercase letters (per CMOS 8.159).

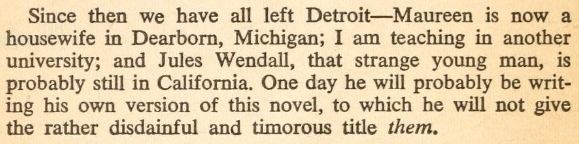

But there is at least one exception. The novel them, by Joyce Carol Oates (Fawcett Crest, 1969), is usually so styled, but not because of the cover or title page. The publisher’s preference is made clear on the copyright page and elsewhere, including in this final paragraph of the “Author’s Note,” which hints at the significance of the lowercase t:

Though it wouldn’t be wrong to apply an initial capital, we’d support an exception in that case, however odd it might look:

Oates, Joyce Carol. them. Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Crest, 1969.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Why are prepositions (and other such words) lowercase in titles in Chicago style (per CMOS 8.159)?

A. Except as the first or last word in a title, prepositions (and a few other categories) remain lowercase in titles in Chicago style—and in most other styles—because they’re not considered important enough to capitalize.

The first edition of the Manual (published in 1906) said to capitalize “all the principal words (i.e., nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, verbs, first and last words) in English titles of publications” (see ¶ 37). In the examples of titles that followed this advice, only the, and, of, and on—one article, one conjunction, and two prepositions, all of them short—were lowercase.

This advice remained mostly unchanged until the twelfth edition (1969), the first one to name the lowercase exceptions—and to clarify that length isn’t a factor: “Lowercase articles, coordinate conjunctions, and prepositions, regardless of length” (7.123; emphasis added).

A new paragraph demonstrated the rule and included a title with a very long preposition: “Digression concerning Madness” (12th ed., 7.128; emphasis added). Many other styles, including AP, APA, and AMA, would capitalize “concerning” in a title simply because it’s long (four letters is a common limit for prepositions).

At least one style guide, New Hart’s Rules (2nd ed., Oxford, 2014), takes a less strict approach—for example, recommending lowercase for possessive pronouns and allowing for exceptions based on appearance: An Actor and his Time and All About Eve (“a short title may look best with capitals on words that might be left lower case in a longer title” [8.2.3]).

So the rules have always been a little bit arbitrary. But Chicago and most other styles include guidelines that are designed to help writers and editors make quick decisions rather than considering the words in a title on a case-by-case basis. For more on this subject, see “Is ‘Is’ Always Capitalized in Titles?” at CMOS Shop Talk.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. How should the phrase “out of” be capitalized in a title or heading?

A. The phrase “out of” is listed as a preposition in Merriam-Webster (among other dictionaries), so it would normally remain lowercase in the middle of a title or heading following Chicago style.

But even as part of the phrase “out of,” the word out tends to read like an adverb (or sometimes an adjective, depending on whether it follows a noun or verb form), which may be why publishers seem to want to capitalize it in the phrase “out of” more often than not—as in the titles Bat Out of Hell (the album by Meat Loaf, featuring a song of the same title) and Getting Out of Saigon (a book by Ralph White [Simon & Schuster, 2023]).

Nonetheless, Chicago style would be Bat out of Hell and Getting out of Saigon. This would work well for Meat Loaf’s sixth studio album: Bat out of Hell II: Back into Hell. If nothing else, “out of” is then consistent with “into.”

[Editor’s update: As several of our readers have been kind enough to point out to us, it would make more sense in the Saigon title to treat “getting out” as a phrasal verb than to treat “out of” as a phrasal preposition. The result—Getting Out of Saigon—capitalizes the word “out” as an adverb (per CMOS 8.159, rule 3), putting the emphasis where it belongs, on Getting Out.]

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. CMOS 14.195 explains how to include the headline names of regular columns or features in a footnote citation, but how should they appear if mentioned in the main text: italicized, in quotes, or roman? Thanks!

A. Use roman and initial caps in both contexts—for example, when you mention or cite the article “My Spectacular Betrayal” in the Modern Love column in the New York Times.1 The lack of quotation marks helps keep the name of the column distinct from the article title. See also CMOS 8.177.

__________

1. Samantha Silva, “My Spectacular Betrayal,” Modern Love, New York Times, May 19, 2023.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]